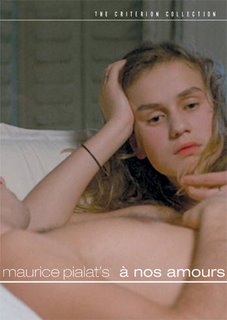

À nos amours

Directed by Maurice Pialat

Written by Arlette Langmann, Maurice Pialat

À nos amours is a powerful, uncomfortable film that is reminiscent of the work of American director John Cassavetes. It presents an invasive view of a family torn apart when the father, played by director Maurice Pialat, leaves the home. His departure coincides with the sexual awakening of his fifteen-year-old daughter Suzanne. She temporarily escapes the madness of home through affairs, unaware that her actions are fueling the discontent.

The film opens with Suzanne, a beautiful young girl away at summer camp, rehearsing her lines for a play about love. A young man is eager to take her out on a boat ride. When we learn that he is her brother, what was witnessed in the previous scene becomes questioned, which is what Pialat wants the viewer to do with every relationship presented.

Suzanne sneaks away to visit with her boyfriend Luc. He wants to have sex with her, but she stops him, leaving him disappointed and suspicious that she no longer wants to be with him. She assures him things are fine between them. Later, she goes to a dance and meets an American boy. She gives him her virginity, but is upset when he ignores her the next time he sees her.

Back home, Suzanne and her friends spend a lot of time missing school. One night she announces she is going out with friends, but her father suspects something, so he forbids it. She argues with him, so he strikes her across the face, but she goes out anyway. When she returns late, her father is still awake. Instead of the angry parent, they have a conversation as adults. For the first time they are aware of each other as sexual beings, and their relationship is forever changed.

The father leaves the family and while it’s never stated, there is some question as to whether the change in Suzanne brought on his departure. The mother is an emotional wreck, lashing out at Suzanne violently for coming and going as she pleases. Suzanne is a double reminder of the mother’s lost youth. She scolds Suzanne for sleeping naked and complains that she never should have had children. The brother tries to step up and be a man of the family. He also gets physical with Suzanne. He decries her for being a slut, yet when she asks if he’s jealous, the only response is an awkward silence.

However, it’s not the sex that is important to Suzanne, but the void inside that she fills with it. Yes, she moves quickly from man to man, but the film never shows the sex scenes. We always come in afterwards because those are the moments that tell us the most about Suzanne. The film’s title translates “To Our Loves” not “Lovers”, so it’s natural that her father and her first love, Luc, have the greatest impact on her throughout the story.

À nos amours is tough to watch because the emotions and actions are so raw, but it is a compelling story of a young woman coming of age that is not often seen on screen.

The Criterion Collection provides a second disc of supplemental material that explores the film and Pialat’s directorial style. The Human Eye is a 1999 documentary with interviews of the cast, crew, and a critic. They reveal a great deal about the film and working with Pialat, including how he altered the story without telling the actors. As an actor in the film as well, he would surprise them on occasion to see what they would create. He actually changed a major plot point for the climatic scene, which is a beauty and freedom allowed when creating films on a low budget. No Hollywood producer would have allowed such a drastic change while a scene was being filmed. It’s amazing that it works so well in the film.

There are a number of interviews included with the set: an archival interview with Pialat on the set in 1983; two interviews from the November 1983 issue of Cinematographe with Pialat and cinematographer Jacques Loiseleux; Sandrine Bonnaire, who played Susan, from 2003; and two interviews from 2006 with Catherine Breillat, who wrote the screenplay for Pialat’s 1985 film Police, and Jean-Pierre Porin, who worked with Godard and is now a professor at UCSD.

The film is presented in a new, restored high-definition digital transfer at a 1.66:1 aspect ratio, and the audio is monaural with English subtitles.